της Maria Komninos

Πρώτη δημοσίευση: Αφιέρωμα στον Θόδωρο Αγγελόπουλο από την Ταινιοθήκη του Βελγίου Kinematek και την Ταινιοθήκη της Ελλάδος, Μάρτιος 2014

An internationally acclaimed auteur with a distinct personal style, modernist Theo Angelopoulos made his mark for his epic transpositions of ancient Greek myths to modern settings. Such transpositions are central within his films (Létoublon, 2001:31). On the other hand, grand metanarratives like Marxism, typical according to Lyotard of modernity (Lyotard, 1979/1984: 36-37), form the basis of Angelopoulos’ political statements, along with family woes of heroes inspired by Greek mythology. However Angelopoulos, discussing his epic The Travelling Players (1975), has argued that the way he resolves the contradiction of both portraying his heroes as part of the ancient myth of the Oresteia and simultaneously historicizing them, by placing them in a specific historical period, is the following:“My heroes’ motives are different (than those of the tragic heroes[1] and the ideas that motivate them belong to another historical space. It is “History” which intervenes, alters and changes the heroes. There are contradictions inside the heroes’ characters, but they don’t stem from the psychological level. Their actions are not amenable to psychological interpretation”. Thus Angelopoulos sets up a modernist text in which spectators are summoned to become producers of new interpretations of history, yet within the framework of the grand metanarrative of Marxism. Films like Ulysses’ Gaze of 1995, where an ex-Marxist, tormented by his own family past and the loss of his ideology after the fall of the Iron Curtain, reinvents himself as a modern Ulysses travelling around the war-ridden Balkans of the time, are linear representations either of oedipal trajectories or of the filmmaker’s own self-conscious subjectivity. Although the narrative in Ulysses’ Gaze is set in a postmodern, war-torn Balkan peninsula, the fact that it is structured around the self-conscious gaze of a director identifying with the main character is typical of a modernist, essentially bourgeois signifying practice (Jameson, 1997/2012: 82) and seems to oppose the optimism of avant-garde filmmakers (Komninos, 2001: 107). What, however, may be said to act as catharsis in Angelopoulos is poetry, as exemplified by the film An Eternity and a Day (1998), where the main character finds a bigger, redemptive purpose through his exchange of poetic words with a boy and his quest for meaning in the work of 19th Century Greek poet Dionysios Solomos (Stathi, 2012: 22). The catharsis of An Eternity and a Day culminates in an epic homecoming reminiscent of Bergman’s Wild Strawberries (1957), where the main character returns to his own roots.

Angelopoulos chronicles in his unique style (slow, extended, camera movements and a lyrical sense of the relation between landscape and cinema) this tragic trajectory, mixing the personal and local with the grandest historical narrative. His later films foresaw and reflected on the rise of neo-liberalism and global capitalism, which has led to the current Greek crisis. The Greek tragedy becomes the canvas for Angelopoulos filmic poetry. As Andrew Horton has said Theo Angelopoulos is one of the preeminent modernist auteurs of the last century and thus a major influence for the new generation of the auteurs of Contemporary Greek cinema.

It is remarkable that in the period 2008-13, a number of young directors have emerged who made their mark in the big festivals, Venice and Cannes, and even in the case of Dogtooth was shortlisted for the Oscar for best foreign film. Strella (2009) took the Berlin Film festival by surprise. There was a film by Panos Koutras daring to present a tale of Oedipus transvestite but with style-with undertones of Fassbinder- that was completely original. Dogtooth (2010) by George Lanthimos with a strange tale of incest and incarceration took the prize for best film in Cannes, Un certain regarde, section. Attenberg (2011) by Athena Tsangaris won the award for best female actress (Arianne Labede) in Venice film festival. Plato’s academy (2011) by Philippos Tsitos won the Silver leopard in Locarno and Unfair world , Adikos kosmo (2012) in San Sebastian. Miss Violence (2012) by Alexandros Avranas won the Silver Lion for best director in Venice and his male protagonist Themis Panou, the Volpi Cup for best male actor. I propose that these films of contemporary Greek Cinema can be grouped in three major trends: the “Weird”, the social realist and the modern flaneurs. My question is to what extent the auteurs belonging to these trends are committing a symbolic patricide or tow the line of the great master Theo Angelopoulos.

The “Weird Wave”

It seems pertinent to compare the four “Weird Wave” films with films by modernist Theo Angelopoulos, a defining filmmaker of the so-called period of the “New Greek Cinema”. We will show that, compared to the modernist films of Angelopoulos, these four films mark a departure from the classical oedipal scenario, both as the driving force of their narratives and in their portrayal of family woes. Finally, we will demonstrate that, through postmodern practices like pastiche and the use of language forms like gay slang and non- or preverbal expression often mimicking animal cries, the four “Weird Wave” films do not only defy poetry, crucial in both Greek literature and the auteurs of New Greek Cinema, but they also ultimately challenge oedipal family structures and language-based narrativity.

Thus the contemporary Greek “Weird Wave” seems to combine an adoption of post-modern ways of expression[2] with a reversal of oedipal scenario[3]. While oedipal conflicts are central within its structure, they seem to be challenged in a number of “postmodern” ways. In the Greek “Weird Wave” subjects are, in postmodern style, desubstantialized (Stam, 2000: 301), as the wholeness of old egos, including that of the auteur, transmutes into a fractured construct fashioned by the media. This media-conscious cinema is largely ironic towards its characters (Stam, 2000:304) and linear narrative is challenged by pastiche, probably the most typical expression of postmodernism (Stam, 2000: 304). Pastiche is here understood as non-ironic mimicry and random cannibalization and mixture of styles and genres of the past (Jameson, 1991:17), confounding highbrow and popular culture (Huyssen, 1986: 216-217). And finally, traditional language in the Greek “Weird Wave” defies narration by diffusing into non-verbal or preverbal seemingly unconnected and not necessarily communicable language games (Lyotard, 1979/1984).

Strella is at first look a narrative, plot-driven film with an oedipal scenario. After 14 years in prison, Yorgos, a middle-aged man, begins a sexual relationship with Strella (Mina Orfanou), a young transsexual. Yorgos had been jailed for having killed his nephew, who had sexually assaulted his son. In the course of the film it turns out that Strella is actually Yorgos’ son, the one that had been assaulted, now a transsexual, and that she had purposefully pursued a sexual relationship with her father. When Yorgos finds out, a clash occurs between father and child. Eventually though, in what seems to be an ironic happy end, defying any known resolution of the Oedipus complex, father and child decide to live the rest of their lives as a couple, sharing their home with a number of other transgendered people. Thus, contrary to the films of Angelopoulos, in Strella the oedipal condition evades its reaffirmation. Furthermore, Strella does not always follow a typical plot-driven narration. The main form of narration in the film is pastiche; mixing in Almodovar’s fashion modernist melodrama with Fassbinder-esque queer film clichés, along with Disney-like cartoon sequences of Yorgos dreaming of himself in a typical queer way as a squirrel running around free in the woods. Yorgos thus appears as a fractured gay; however violent subject heterogeneously constructed by his macho tradition, but also by pop culture and the media. And finally, probably the most defining form of dismissal of classical oedipal structures in Strella is the use of language. Gay slang is, along with gay kitsch aesthetics, ubiquitous in the film. In a defining moment, where Greek familial tragedy and the ensuing oedipal structures seem to simultaneously collapse, Mary, an old, dying transsexual acting as Strella’s mother, admits to having had a sexual relationship with her uncle, while warning her “daughter” that, according to ancient Greek sissies of the likes of Sophocles and Euripides, sexual union with one’s father is “hubris” (an insult to the gods). To remember Lyotard (1979/1984: xxiv), Mary’s contradictions seem to combine an incompatibility of language games, typical of postmodernism, which defy rational speech acts. And while still there, the subjective view of gay auteur director Panos Koutras, as well as traditional plot with a beginning and an end, seem to be lost within the heterogeneity of genres and the irony of an apparently happy end which would never be possible in the grandiose formalism of the auteurs of New Greek cinema.

Dogtooth portrays a family home where the children, well into their late teens or even twenties, are kept by their parents (Christos Stergioglou, Michele Valley) in typical oedipal terms completely confined from the outside world. The children are taught false word meanings aimed mainly at appeasing their urges for freedom and sex (i.e. they are told by their parents that “excursion” is a highly durable material used to make floors and that the word “cunt” means “large lamp”). The challenging of this oedipal scenario comes through Christina, a young woman brought in the home by the father to cater for and thus appease the son’s sexual drives. Christina asks the older daughter (Angeliki Papoulia) to perform cunnilingus to her. The older daughter accepts, initially on condition that Christina gives her a headband and later some videotapes. After watching the videotapes, the older daughter changes considerably. She starts heterogeneously reconstructing herself through the media she has watched, performing in unintelligible and nonverbal ways scenes from the videotapes, which as we infer are of the movies Flashdance, Rocky IV, Jaws, and an unspecified one by Bruce Lee. Like Yorgos in Strella, the subject “older daughter” in Dogtooth is constructed discordantly by popular culture, through a performance of a pastiche of various films, whereby actors’ lines with no apparent connection to one another mix with a boxing scene from Rocky and a violent reworking of choreography from Flashdance. These scenes culminate in the film’s ending, where the older daughter locks herself in the boot of her father’s car, leading her way out of the family home and into freedom or asphyxiation. We never find out if she survives. As in Strella, the dubious ending seems to overturn the oedipal scenario along with pastiche, references to popular culture and a use of language which alludes to a “new speak”, conditioning the children like Pavlovian dogs.

Similarly, in Attenberg, Marina (Arianne Lebede), a young woman living a desexualized life in a boring, sterile industrial town (Aspra Spitia)[4] with her dying father, seems to find meaning in her mimicry of the animal sounds she hears in the documentaries of Sir David Attenborough that she regularly watches. She engages in this non-verbal mimicry along with her father, to whom she has a strong attachment[5]. Quite often, father and daughter play a language game whereby they hurl to each other random words with no apparent connection. In this mixture of animal sounds, unconnected language morphemes and desexualized father-daughter relations, whereby a father is pictured without a penis, oedipal scenarios demanding a linear narrative and sexually potent parents are severely challenged. The whole film seems more like a collection of sketches involving a certain number of people than a narration of their life-stories. Pastiche makes its presence again, both in the mimicry of Attenborough’s documentaries and in the dance-like walks, alluding to French Nouvele Vague[6], which Marina takes along with her sexually promiscuous friend, Bella. Popular culture appears to have infiltrated Marina, too, as Attenborough’s documentaries have decisively formed her along with songs of the synthpunk band Suicide, which appears to be about the only music she listens to. Yet pastiche-inspired, non-linear narrative is reversed when Marina’s father is about to die. Only then does the classical Oedipal scenario emerge, as without her father, she consummates at last her relationship with an engineer (George Lanthimos) and becomes a sexually active woman.

Miss Violence, is the story of a fourteen-year-old virgin who on the day she turns fourteen commits suicide. This acts a catalyst to reveal a monstrous Oedipus (Akis Panou) who is having an incestuous affair with his elder daughter, and having fathered his grandchildren not only he has sex but he also prostitutes them. This violent reversal of the oedipal scenario leads to full fledged tragic telos. The children have to live through a suffocating contradiction a father/grandfather who is insisting that they are strictly committed to performing their school duties yet on the other hand dresses them like Judy Foster in Taxi driver to have them prostituted. The only person who defies his will is his granddaughter who by committing suicide forces the mother ( Reni Pittaki) to take vengeance and liberate the family. Thus the oedipal scenario is reversed not through the action of children but from the action of the wife who revolts against the paternal oppression but it’s doubtful whether she will be able to heal the wounds and keep the family together.

The social realist trend

Films such as Plato’s academy, Homeland (2010), by Syllas Tzoumerkas, J.A.C.E ( 2011), by Menelaos Karamaghiolis, Correction (2007), by Thanos Anastopoulos are nearer social realism with auteurist overtones and diverge from the postmodernist tropes of the “weird wave”. Though these stories are also steeped inside the economic crisis that is tearing Greek society apart they adopt more conventional narrative forms to present their texts and they can’t achieve the unique style which has marked the oeuvre of Angelopoulos. Though we should note that compared to the third trilogy of Angelopoulos, the trilogy of the frontiers these films are similarly reflecting on themes which are inspired the current crisis neo-liberalism and global capitalism.

Plato’s academy that was shortlisted for the Felix Price, tells the story of Stavros (Antonis Kafetzopoulos) who spends his time with his three over forty male friends worrying about the Chinese immigrants who are invading their quiet neighborhood, and teaching their dog Patriot to bark at passing Albanians. Things take an unexpected turn when Stavros’s mother (Titika Saringouli) recognizes a passing immigrant Marenglen (Anastas Kodzine) as her missing son. She also starts talking Albanian. Stavros will realize when his mother dies that in the words of Filipos Tsitos: “That he has for a long time defined himself as being Greek. He has not asked himself if he is happy or not”.[7]He therefore decides to accept his mixed identity and try and win back his girl friend. His friends must also to set aside their prejudices and accept Stavros whatever his ethnic origins. This bittersweet comedy goes against the moral panics orchestrated by the popular press and appeal for dialogue as an antidote to social exclusion.

Correction (2007) by Thanos Anastopoulos is narrative of forgiveness. It narrates the story of a repenting hooligan (Yorgos Symεonidis) who assassinates an Albanian celebrating his team’s victory on the day Albania beat Greece in soccer for the world cup. After his release from prison he finds the victim’s family and puts them under his protection. Until by unexpected twist his secret is revealed to the wife’s victim but who also make a gesture of forgiveness.

This film is in line with other films of contemporary Greek cinema such as Giannaris, Goritsas and Korras and Voupouras focussing on the plight of immigrants with compassion that runs counter to the strong xenophobic feelings that were shared by a small section of the population. Themes that were originally developed in a masterly way by Angelopoulos in the trilogy of the frontiers, which focused on the plight of immigrants in the aftermath of the fall of the Berlin wall.

This film is a sober almost Bressonian tale which went against the grain of moral panics orchestrated by popular press and television. It is note worthy how the device of the footage stored in the protagonist’s mobile acts as a catalyst in similar way as the videotapes act in Cache, by Haneke. In the case of Cache, Georges is feeling threatened when he starts receiving videocassettes, which show that his house and family are under surveillance. Yet the Foucaudian scheme is turned into its head, and the distinction between the surveyor and the surveyed breaks down. In Correction it’s a different matter, the nationalist thugs had recorded the assassination of the Albanian as a heroic did worth commemorating as torturers in Abu Graib recorded their degrading acts. In this new globalised Panopticon no vile act can be performed without some form of recording. These new archives of evil are no longer apocryphal and repressed but instead are accessible and preserved acting as memorabilia of the “banality of evil”.

Postmodern flaneurs

Greek women directors had indeed to cope with a heavy legacy, as two of the leading lights of NGC were Tonia Marketer and Frida Liappa. It is my assessment that their oeuvre influenced a number of emerging women directors such as Evangelakou, Flessa, and Malea who resorted to comedy for painting the discontents and pleasures of Greek women in the new century. However in the case of both Kostantina Voulgari and Stella Theodoraki there is return to a more melancholic climate. In their case contrary to Angelopoulos heroines, who are more or less reflections of the male phantasies of the protagonists, women take an active part in directing the plot and their films are embodying a new form of feminine self-awareness.

Voulgari sets her second film Congratulations to the optimists? In the famous Athens neighbourhood of Exarchia. Her heroine Electra (Maria Georgiadi), who has graduated from a top UK University lives there and refuses her parents (Themis Batzaka, Dimitris Piatas) suggestions that she should look for a “suitable job”. Her boyfriend has been arrested for being part of an anarchist group. Although Electra sympathizes with his standpoint when she visits him in jail she feels crushed by his reductionist view of things. Her parents are also totally trapped by their academic background. Electra only feels happy with the young boy whom she babysits and for whom she sometimes acts as a surrogate mother. This film as the Daughter is also a tale of rite de passage as Electra on the one hand strives to stop being an adolescent yet at him same time she struggles to sustain her child like optimism and her walks in the city help her discover that the revolutionary spirit is kept alive.

Theodoraki a French trained director in her third film Amnesia diaries (2012) won the Greek film academy award for best documentary. As the director herself writes: “Amnesia Diaries started out when I discovered some long-forgotten Super 8 footage. My Super 8 films had gotten stolen while I was a student and, eager to put the incident behind me (it had upset me greatly), I had totally forgotten about the leftover material. Among oxidized colors and faces whose identity had faded over time, my first contact with the Super 8 transfers was a real shock to the system. I immediately got curious about what would happen if I juxtaposed the 25-year-old material with contemporary images, so I started documenting everyday life and found myself getting carried away as the credit crunch deepened.”[8] This personal project allowed the director to combine both what Derrida has called “archive fever” with new ways for combining recorded memories and new material from both private and public events in Athens for sculpturing time. These diaries act as logbook of the director’s itinerary from Crete, to Paris, Australia, London and then back to Athens. The film is a journey through time and a journey through continents, while the author observes and comments about her life in periods of love and happiness and in periods of loss and mourning. Theodoraki establishes a personal style which marks her as a post-modern flaneur.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Huyssen, Andreas, After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1986).

- Maria Komninos and Yannis Lambrou “Questions of Postmodernism and Greek cinema: Language and Family in the New “Weird Wave” paper presented in the third Annual London Film and Media Conference: The pleasures of the spectacle, Institute of Education University of London, UK 27-29 June 2013.

- Létoublon, Françoise, ‘The Odyssey of Angelopoulos’, Gazes in the World of Theo Angelopoulos, ed. Irini Stathi (Thessaloniki: Thessaloniki International Film Festival, 2001), 31-41.

- Lyotard, Jean-François, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, trans. from French Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984).

- Mulvey, Laura, ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, Visual and Other Pleasures (London: Palgrave, 1975/1989), 14-26.

- Stam, Robert, Film Theory: An Introduction (London: Blackwell, 2000).

[2] Two basic demands of postmodern art, if we follow Lyotard’s famous essay The Postmodern Condition of 1979, are that the postmodern puts forward “the unpresentable in presentation itself” and that “the work a [postmodern artist] produces [is not] governed by pre-established rules and… [should not] be judged according to a determining judgment, by applying familiar categories to the text or to the work. See Maria Komninos and Yannis Lambrou “Questions of Postmodernism and Greek cinema: Language and Family in the New “Weird Wave” paper presented in the third Annual London Film and Media Conference: The pleasures of the spectacle, Institute of Education University of London, UK 27-29 June 2013.

[3] In order to theorize the Oedipus complex within realist film narrative, which seems to deny postmodern demands for a non self-conscious putting forward of the unpresentable, one should look into the work of psychoanalytic film theorist Laura Mulvey. As Mulvey claims in an essay pivotal to contemporary film theory, ‘sadism demands a story, depends on making something happen, forcing a change in another person, a battle of will and strength, victory/defeat, all occurring in a linear time with a beginning and an end’. True to Freud, Mulvey equates in Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema the narrator, or, in cinematic terms, the filmmaker, to a superego sadistically controlling its subject matter, therefore producing a story with a beginning, a middle and an end. ibid

[4] The location is emblematic since it is the site of Pechiney aluminium factory, which was one of the major industrial plants and had played a crucial role in Greece’s industrialisation in the 60s. Today the plant has been sold and the area is a landmark of white elephant, as Greece is plunging into a neo-colonial u-turn to backwardness. As a shooting ground it provides Tsagari with the opportunity to shoot in space resembling Pescara in Antonioni’s Red Desert.

[5] In characteristic scene Marina asks her father if he ever thinks of he nude. The father denies of ever having such fantasies since they would go against the incest taboo. Marina after listening to his lecture adds with a low voice « I think of you naked but without a penis». So she is dreaming of a castrated father that could be interpreted as censoring her incestuous desire for her father.

[6] Godard’s Bande a part comes to mind.

[7] Interview of Filippos Tsitos to Valerio Caruso.

[8] Stella Theodoraki interview at Flix.

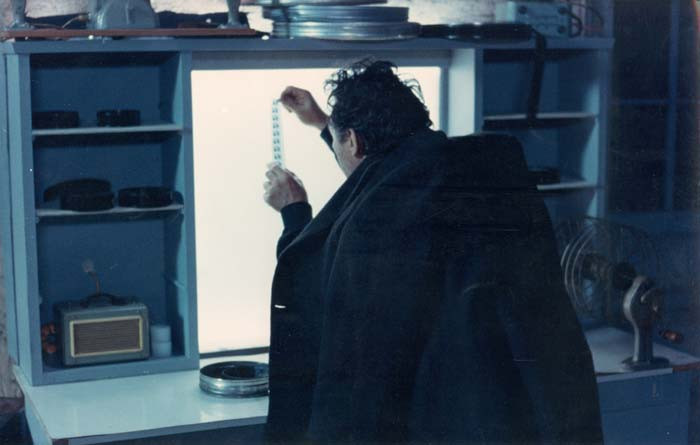

Φωτογραφία εξωφύλλου: Το βλέμμα του Οδυσσέα, 1995, Θόδωρος Αγγελόπουλος